Charting the path to a biologically informed system of mental illnesses

Willa Goodfellow ~ Mar '20

A moonshot exploring the human brain at single-cell resolution

Andrew Neff ~ Mar '20

Written & Illustrated by Andrew Neff

January 2019

5 minutes

He Jiankui's Social Media Manifesto

on Gene Editing

In late 2018, He Jiankui announced on youtube that he produced, or created, or, whatever, the first ever genetically edited human babies. This announcement was met with outright horror and condemnation from the medical and bio-ethical communities. And there are very, very good reasons to condemn this type of procedure as a potential scourge on the human race. But there’s also a reason we’re so excited about Crispr gene editing technology, because, obviously, one day, we hope it can prevent or cure diseases. Below, a couple of reasons why we definitely are not ready to start making mutants. Then a few words from the villainous gene-editor himself, He Jankui, and his alternative perspective on why geneticists have an obligation to mutate.

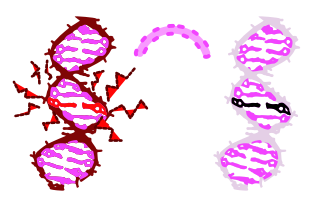

Most commonly, geneticists are hesitant about human crispring (mutating) because crispring one gene always leads to some amount of unintentional crispring of other genes, particularly, other genes that look a lot like the gene you’re aiming for. These off-target mutations, they say, could render genetically-edited children (e-children?) more susceptible to disease. Now, humans do mutate, evolution, remember? Each new baby has an average of about 40 mutations in their 3 billion character genome that can’t be found in either parent (Kong, 2012). If Crispr is going to prove it’s safe, compared to a tolerable risk standard of say, 40 mutations?, it’s got it’s word cut out for it. Studies in animals have in fact shown that Crispr gene editing is extremely precise (Anderson, 2018), that’s part of the reason Crispring things is so vogue today.

But caution, caution is paramount when you’re editing the genes of cells that will be passed onto future offspring. Because, bioethicists tell us, one day, should these e-children have de facto e-children of their own, and those children have children, any mutations could eventually become distributed throughout the wider human population. So caution, say the ethicists, don’t we want to be super-extremely-sure that our technology isn’t causing new diseases before we condemn an unconsenting future humanity to a world of potential e-person diseases?

And then there are the situation specific objections. Like, why did this guy pick a gene associated with HIV, a disease that’s really well medically managed, as opposed to something like Huntington’s Disease, which isn’t? And, like, why announce this on social media and not in a scientific journal? And, did he really inform the parents well enough so that they could understand the risks posed to their e-children, and ultimately maybe that thing about potential species-scale disease-condemnation?

But on the other hand, as a scientist with decades of experience in genetics, you might imagine that He Jiankui has some ideas of his own on the ethical calculation we should be making when considering e-babies. In his youtube video, He lays out 5 core principles for genome editing in human embryos:

1. Geneticists should offer mercy for families in need (悲悯之心) Some people carry genes that, if passed down to a child, could put them at medical risk. If we have the technology to decrease the likelihood of a disease, or prevent it, we should do it.

2. Gene editing should be used only for serious disease, never vanity (有所为更有所不为) He Jiankui acknowledges that gene editing exposes children to potential health risks, although he doesn’t talk about the potentially humanity-dooming public health risk of those genes infiltrating the offspring of organic non-GMO people.

The rest are more cart-before-horse type principles, that is, they don’t have much to do with the decision of whether or not to edit, but instead, how to treat e-people, or who should have access to genetic editing.

3. Respect e-children’s autonomy (探索你自由)

4. Understand that genes do not define people (生活需要奋斗)

5. Gene Editing for All - everyone deserves freedom from genetic disease, regardless of one’s financial situation (促进普惠的健康权).

Want more Brain Science in your life?

Got a dollar per month to spare?

Support Mind & Brain Illustrated today on Patreon.

Mercy for families in need sounds great, we wouldn’t be developing Crispr if not for the ethical promise of providing mercy for families in need. Vanity though, depending on how you define it, could be a troubling issue. In gene editing, it would be vain for a parent to select a child's appearance, their physical fitness, or intelligence. It shouldn’t be about vanity, He says, because vanity doesn’t outweigh the potential health risks to the child. But at the same time, most parents have the right to a healthy child already, they just have to be willing to adopt one. Might we consider the desire to have our own personal children, with our own personal genetics, despite the unknown risk to others, to be a form of vanity?

There is an issue of human rights at stake here that’s being balanced against the precision of Crispr technology, and the medical risk of non-precision. Most geneticists and medical researchers say the amount of uncertainty over the potential health complications of off-target gene mutations is a high cost, too high a cost. He Jiankui says, sure that’s a high cost, but the interests of individual families outweigh those costs in some instances.

What are your thoughts on He Jiankui’s manifesto? Does he have a point in asserting individual rights, and the ethical responsibility of geneticists? Or is the mainstream bioethical communities’ anxiety justified? Bioethicists and He Jiankui may have their positions, but in society at large, and in our minds, this topic is just heating up, preparing for round two. And the fight in round two is going to have to start getting a little nitty and gritty, it’s going to have to start taking in numbers. Is it possible that new Crispr tecniques are sufficiently precise that the benefits of getting rid of a disease will outweigh the likelihood of a random mutation causing another disease? Let us know if you have any information on this, we need some grit, your perspective will be essential as this debate progresses.

References:

-

Anderson, Keith R., et al. "CRISPR off-target analysis in genetically engineered rats and mice." Nature methods (2018): 1.

-

Kong, Augustine, et al. "Rate of de novo mutations and the importance of father’s age to disease risk." Nature 488.7412 (2012): 471.

Images:

-

Person - María Cruz